Olympia’s Story

This is a guest post written by Cora Hanlin, an active member of the axolotl community and a volunteer and foster here at LibertyLand Axolotl Rescue. This is the story of Olympia, one of Cora’s axolotls, and the challenges she has faced during her short lifetime.

Sharing this story has many purposes. I am advocating for the following things:

The removal of axolotls in pet stores (particularly large chains) and that they be forbidden from accepting surrenders/oops clutches

Adequate training for exotic vets to treat axolotls (beyond just recommending euthanasia)

Research into this species that is not related to regeneration

To highlight the flaws in the axolotl community that result in us failing these creatures so we can modify our approaches

I will not name any businesses or people, but I will be including photos. There are specific scenarios that have failed Olympia (and copious other axolotls) in more ways than others, but this is a holistic evaluation of where she has been failed, and why, and a push to correct as many of these circumstances as possible.

Olympia and Ophelia

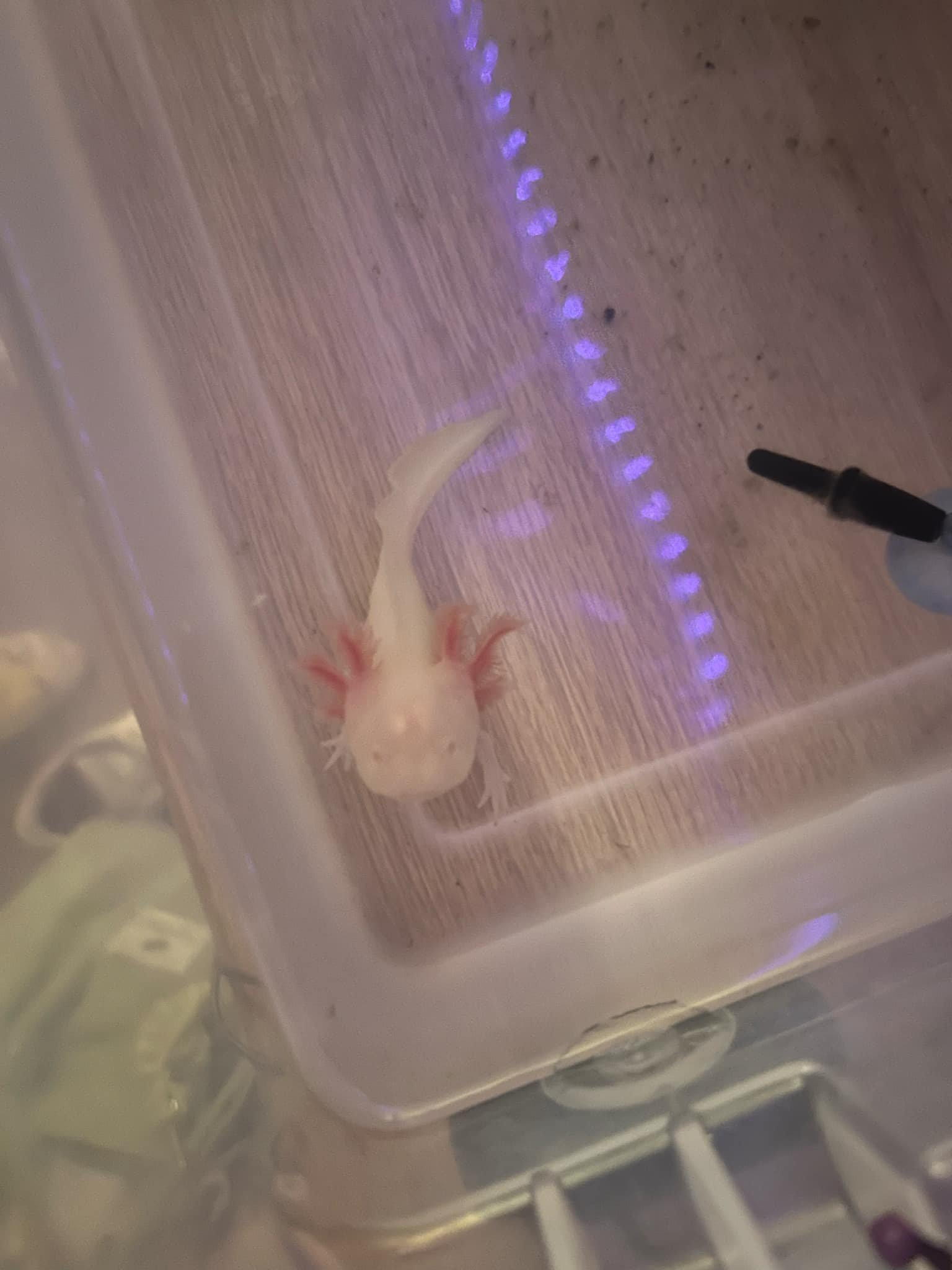

Olympia is an approximately 18 month old female axolotl (pictured above). Her morph is melanoid albino. Ophelia is Olympia’s genetic sister; they are clutch mates (from the same batch of eggs).

At the time I picked up Ophelia, I will admit I was naive. I was not in the axolotl community whatsoever; I didn’t even know another person that owned an axolotl. I was enraptured with the tank of babies as I’d never seen juveniles so small before. I did not know what I know now to recognize how sick and mistreated they were. A pet store is not a place to support, and I do not recommend this now (if looking for an axolotl, please consider a reputable breeder or a rescue).

This was in November of 2023. Below are the images of the tank they were kept in. The first image is from November, the others are from March. I will note that sand is not safe for juveniles under 5-6 inches, the fish in the tank posed several health risks to the juveniles, the tank was far too high in temperature, and they were feeding approximately 25 juveniles a single cube of bloodworms a day (bloodworms hold little to no nutritional value for axolotls).

Shortly after picking up Ophelia, I realized she was very thin, and she had a fungal infection on her gills. We will not pick apart Ophelia’s story today, but to summarize: the mistreatment the pet store made her endure as a juvenile stunted her growth and resulted in her being immunocompromised. She gets chronic fungal infections, and they tend to be more stubborn to treat than when other axolotls present with fungus. I did not pick up Olympia until 5 months later. She spent about 6 months under the pet store's care.

Below is an image of Ophelia upon pick up (prior to her infection popping up to a noticeable extent).

Ophelia following pickup from the pet store.

Meeting Olympia

In March of 2024 I ran out worms. I went back to the store, and I intentionally stayed away from the axolotl tank. I had already pleaded with them to lower temperatures and remove the sand to no avail. One of the employees in charge of their care learned I own axolotls, and asked me how to cool the tank. I told him if he was asking me this question he should not be allowed to sell them (as he cannot provide adequate care information, or even adequate care, period). I added that cooling a tank was not rocket science; fans, frozen primed water bottles, a chiller; all things someone working in the aquatics department should know.

My boyfriend went to look at the tank, and he called me over. I originally told him no, I couldn’t bear to look at how sick they were, and I didn’t have room at the time for a third axolotl.

“Is she dead?”

I was horrified at what I saw. Out of the approximately 25 babies from the clutch, only 3 remained, and in incredibly worse shape than when I had picked up Ophelia. Olympia looked dead. She was on her side at the very front of the tank. She was 3.5 inches long, emaciated (as skinny as possible without her being dead), anemic. She had a broken arm, a fungal infection, and next to no filaments left on her gills (the fish they had them housed with were nipping the filaments off). I told him she looked dead, yes. Then she moved and she fought so hard to get to the top of the tank for air, and then she fell.

He asked me to save her, and I couldn’t say no. I couldn’t bear the thought of turning my back on her knowing she didn't have much time left. I called the aquarium specialist over, and I explained that she was incredibly sick. I explained I had some rehab experience and was willing to take her (hopefully at no charge).

He said, “No, she's not sick. She’s just a different type. If she were sick she would not be for sale, and we would take her to a vet.”

I commented that they do not come in white, that that is a sign of anemia. My boyfriend interjected that if his statement were true she would have seen a vet a while ago.

We bickered for probably 25 minutes before I knew he was not going to just let me take her. They are quite cheap at pet stores, and I basically decided it was worth it to try and save her life.

He was NOT gentle in taking her out of the tank (what I think broke her arm), and once in the bag he shook her aggressively and said, “Eh, I think she’ll live. If not, we'll replace her.” Even just from holding the bag I knew the water was far too warm for her. The image below is the day I picked her up.

Olympia, following pickup from the pet store.

I will cover her rehab experience shortly, but first I would like to discuss what happened with the pet store…

I had previously reached out to MSPCA (my state's animal cruelty prevention organization) about the state of the axolotls in the store's care after getting Ophelia, and seeing the deterioration of the juveniles over those 5 months. I had hoped that because the species is listed as endangered and near extinct, there would be protection for these babies. The answer I received was that although protections exist for the species, they do not apply to the captive bred population. I filed several formal reports of animal cruelty, with photo evidence (I included the name of the store, the location, and the names of the employees I spoke to).

At first I was directed to a local rescue. When I called she said she had no jurisdiction over a pet store, especially for an animal that was not a dog or cat, but said she wanted to help. I forwarded her the information and images I provided to MSPCA. She was horrified, and she contacted the exotic vet that works with her rescue organization. The vet evaluated Olympia and said she was anemic, emaciated, infected with fungus and possibly a bacterial infection, and that she would not have lasted two more days under the store’s care.

I worked with this rescuer for some time, going back and forth between MSPCA and her. They directed me to many organizations, almost all of which said they also had no jurisdiction or even knew what an axolotl was. In the end, it was the Environmental Police and a different local rescue that went to save the remaining two juveniles. I never heard if they made it, but there is not much hope in my heart for them given what I saw (signs of death include pinned back legs, an open mouth, and swelling of the body and neck that indicates organ failure; some of these signs I saw in the juveniles prior to their rescue).

It took 6 months from my first report for those juveniles to be rescued, and the store was not allowed to sell them again. During those 6 months, I returned to the pet store several times; I created care guides for them to provide customers, I included photo and documented evidence of how they mistreated the axolotls, and I pleaded with them to modify their care. The aquarium specialist yelled in my face and said, “Enough! I’ve heard enough! Leave! Go! Now.”

This was not the first unpleasant interaction I had with that employee. I asked to speak to his manager, and she ignored me. She said he (the employee) knew more than she did, so who was she to question? I left and I sat on the phone for several hours reporting him (with his full name and job title) and the store. He was fired.

Rehabilitating Olympia

I did not name Olympia for two weeks, because I feared she wouldn’t survive. I fed her “worm chunks” which are bite sized pieces of Canadian nightcrawlers, as well as Repashy Grub Pie for additional nutrients. She could not swim well at all, but she ate for me that very first day and I knew she may have a chance. I treated her for fungal infection, and I did a parasite treatment on her since she was housed with so many axolotls and fish.

Olympia’s first pop of color after weeks of discoloration due to anemia.

It took 3 weeks before any color came back to her. She grew 2 inches in the first month, but has since grown incredibly slowly, with several delays when she gets sick. It was a long road of recovery for her. She stayed in her tub for a little longer until her new tank was ready, and she was big enough to live with her sister.

She thrived in her tank for about 6 weeks before I noticed the first symptoms of what would be an underlying internal bacterial infection. I was told she was sensitive to nitrates (which I keep lower than most people because Ophelia gets fungus with regular level nitrates), and so I tubbed her with a little methylene blue for a few days.

The rash on her arm cleared up, and I put her back in. She was good for a week, and I left for a 4 day trip. When I returned her rash was back, and the filaments on her gills turned solid white. The filaments fell off shortly after in patches until she had relatively bare gills. I tried methylene blue for a week before someone recommended an antibiotic.

I contacted a vet. They took one look at her and told me to euthanize.

I tried one antibiotic and she just started declining so rapidly. Her skin turned red, she was veiny, she was losing weight rapidly. She was refusing food, and most of what she ate she could not keep down. I contacted a vet. They took one look at her and told me to euthanize.

I was well experienced with rehabbing at that point and knew she was not showing a single sign of dying. She was not well, she needed help, but she was not on death’s door. I did not call the vet back to schedule the euthanaisa. Below are some images of Olympia’s first bacterial infection.

I could not believe they would not help me. I cried at work and in my car throughout the day knowing she may not make it and that the help I tried to obtain said it was too late.

I got a second opinion from a vet tech, who agreed with me she was not well, but that euthanasia was not a good recommendation at this point. She said she would get me antibiotics if we scheduled a consultation. She was not able to schedule the consult, and I powered through with the two antibiotics I had.

Olympia spent about 9 weeks total in the tub before I felt she was well enough to return to her tank. I kept her separated from her sister temporarily to allow her space to finish healing. And she did heal, she gained weight, her arms healed, and she even grew.

Beginning to suspect compromised immunity

From September to December she was so well and happy. I thought we were in the clear. I checked her arms daily for that rash (mostly due to anxiety it would come back). Then, I fed her one night and her arms were clean, but the next morning I could already see the deterioration and blisters. I got her into a fresh tub while I contacted others to figure out the best course of action.

At this point, I had realized Olympia is immunocompromised (like her sister), but is prone to bacterial infections instead of fungal infections. I started her on methylene blue and Kanaplex until I could determine if something else was better.

I will preface this next section with this: I am now very ingrained in the axolotl online community. I admin or moderate several support pages, I volunteer with a local rescue to rehabilitate and rehome axolotls.

I spent the entirety of the next day doing a few things:

I reached out to the people I believed may know anything about immunocompromised axolotls,

I did my own online research for similar information,

and I contacted a vet in the event I required stronger antibiotics for Olympia’s latest bacterial infection.

The goal of my multifaceted approach was to obtain any available information on compromised axolotl immune systems, and learn how I can set her up her own tank that will be supportive to her health but still enriching.

I understood that many of the people I spoke to do not agree with one another in general. In my pursuit for the information I needed I had realized that even if I was capable of putting her health and future above the social drama, no one could look past it.

I felt as if everyone was so outraged by others' recommendations they could not see Olympia, and my need to create a good future for her.

Olympia and Ophelia together in their cycled tank.

I felt as if everyone was so outraged by others' recommendations they could not see Olympia, and my need to create a good future for her. I was aware not all of the information would be accurate or reliable, but when there’s no info available for me to come about on my own, I needed to make an informed decision. Informed decisions require information, and I was finding none.

At that point, I felt as if I was back to square one, but now I’d been given an absurd amount of differing diagnoses and treatments.

I was—and continue to be—outraged at how difficult it is to support axolotls due to people not being able to put the animals’ health first (this applies to a multitude of fields and communities).

This one axolotl has suffered more in her approximately 18 months than most axolotls I see day to day, and all because people have not cared for her the way she required.

These are magnificent, wonderful, fascinating critters AND they have their limits. They are not magic, they are biological beings. They do not have a voice to tell you what is wrong and they cannot advocate for themselves. No axolotl life is worth a sale. No axolotl life is worth someone’s husbandry preferences. No axolotl life is worth a surprise. No axolotl’s life is above social drama. They’ve suffered enough. Olympia has suffered enough. They deserve our support. We must advocate for them.